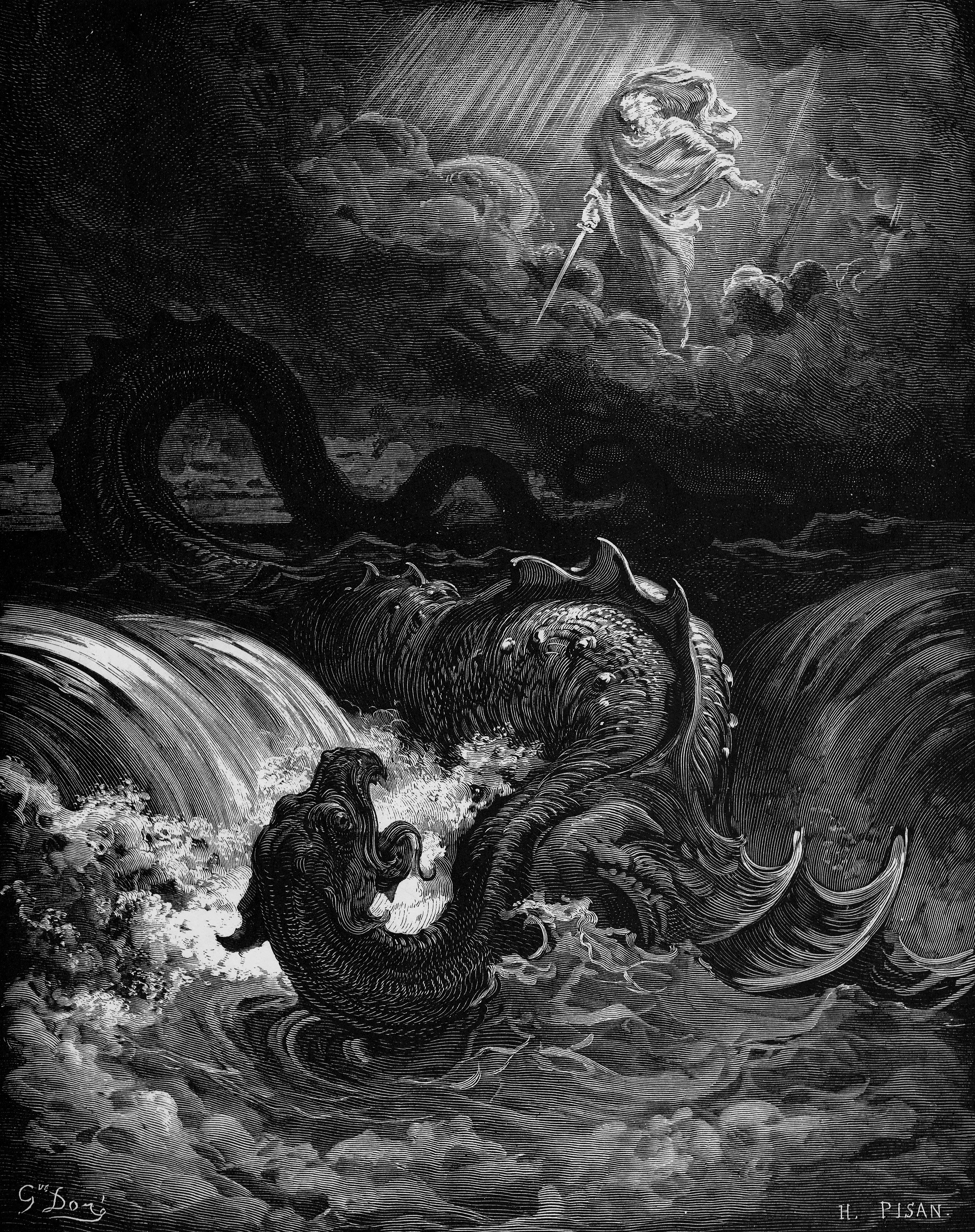

Entering that gable-ended Spouter-Inn, you found yourself in a wide, low, straggling entry with old-fashioned wainscots, reminding one of the bulwarks of some condemned old craft. On one side hung a very large oilpainting so thoroughly besmoked, and every way defaced, that in the unequal crosslights by which you viewed it, it was only by diligent study and a series of systematic visits to it, and careful inquiry of the neighbors, that you could any way arrive at an understanding of its purpose. Such unaccountable masses of shades and shadows, that at first you almost thought some ambitious young artist, in the time of the New England hags, had endeavored to delineate chaos bewitched....

A boggy, soggy, squitchy picture truly, enough to drive a nervous man distracted. Yet was there a sort of indefinite, half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it, till you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvellous painting meant. Ever and anon a bright, but, alas, deceptive idea would dart you through.—It's the Black Sea in a midnight gale.—It's the unnatural combat of the four primal elements.—It's a blasted heath.—It's a Hyperborean winter scene.—It's the breaking-up of the icebound stream of Time. M.D.Just imagine Ishmael in the Spouter Inn trying to puzzle out this painting. We of the 21st century have long since grown accustomed to, and often weary of, abstract expressionism. In Melville's day, it was still science fiction, though he anticipates it so well that we can easily imagine him as a 20th century art critic first stumbling across the works of Kandinsky or Pollack, a sudden shudder running up his back - shocked, disturbed, yet somehow exhilarated - recognizing something brand new: the "breaking up of the icebound stream of Time" or "chaos bewitched" indeed. Unlike his colleagues, he wouldn't have thought the artist merely a mad fool, as many critics considered Melville himself. Instead, for better or worse, something inside him would have shifted and new worlds would have emerged from the chaos.

Blue (Moby Dick)

by Jackson Pollack